The Percentage of Construction Workers Saying “I Quit” a Sign of the Times

Friday, April 5, 2019 by Zelman & Associates

Filed under: homebuildingmacro housing

In 2018, the national unemployment rate averaged 3.9%, the first year below 4.0% since 1969, which has been a positive for wage growth and potential entry-level homebuyers. However, the other side of that coin has been a shortage of labor in both quantity and quality. Per a monthly survey conducted by the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB), 23% of respondents in 2018 cited labor quality as their single biggest problem, the highest share over 46 years of data.

Unfortunately, the labor tightness is particularly acute in the construction sector. According to our monthly survey of private homebuilders, the cost of labor was rated 83.0 on a 0-100 scale, ranking highest of the 13 labor and material categories that we track for the fifth time out of the six years spanning the housing recovery. This is despite construction volumes remaining depressed relative to historic norms.

To analyze this further, we utilized data from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Among many data points, in this survey the BLS tracks the percentage of workers that are unemployed and voluntarily quit their prior job, including segmentation by the industry of occupation.

To us, looking at construction-related employment in absolute units is challenged by the fact that illegal workers were far more common during the peak of the last housing cycle from 2002-06, and it is unlikely that this labor supply was tracked correctly then or has been since. However, we believe that the quit rate would better capture the supply-demand effects in the market, even if illegal workers were not counted correctly.

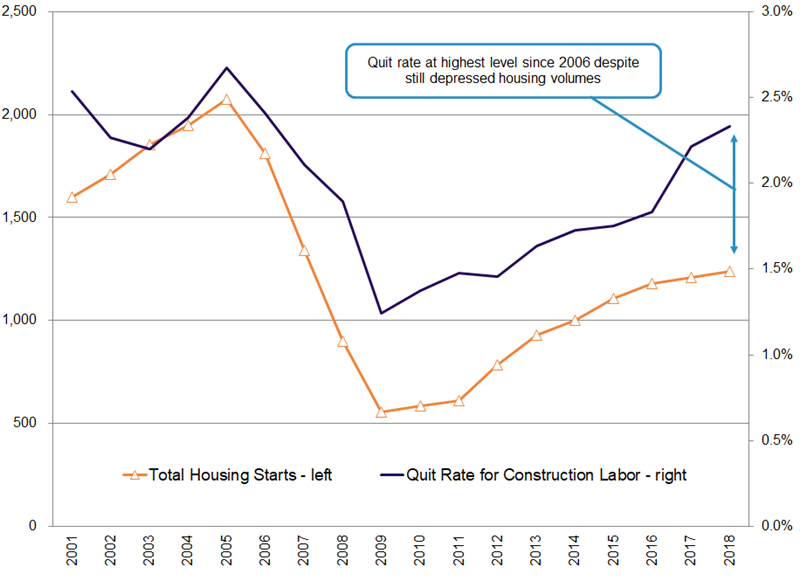

For the construction sector, 2.3% of workers willingly quit in 2018, increasing for the sixth consecutive year. From 2001-18, this ratio averaged 2.0%, meaning that the current propensity to quit is 18% higher than witnessed over history.

Conversely, there were 1.24 million total housing starts in 2018 across single-family and multi-family projects, which almost exactly equals the average from 2001-18. In 2003, housing starts were 49% higher than last year, and yet the quit rate of construction workers was 10 basis points lower than last year. Over the 18-year history of the data, there has never been a bigger disconnect.

According to our conversations with industry contacts, construction labor supply is most hindered by tighter immigration policies that appear unlikely to change in the near term and young adults being underrepresented in the industry. On the latter point, we calculate that only 19% of workers in the construction industry are younger than 30, lower than all other industries at 25%. The differential between those two figures has averaged 520 basis points over the last six years versus being close to parity from 2000-05. From all angles, it is difficult to foresee a path of resolution to the current shortage of qualified labor capacity.

Friday, April 5, 2019 by Zelman & Associates

Filed under: homebuildingmacro housing

Looking for More Insightful Content?

Explore our Researchaffordabilityapartmentsbaby boomersbuild-for-rentconstruction lendingdemographicsentry-levelexisting home saleshome improvementhome pricinghomebuildinghomeownershiphousehold formationhousinghousing startsinstitutional investorsinterest ratesmacro housingManufactured Housingmillennialsmortgagemortgage ratesnew home salesreal estate servicesrefinancesg&asingle-family rentalstocksstudent debtsupplysurvey